Bez’s Blog # 17: “US Population Health Emergency”

I worked for three decades as an emergency (ER) physician. I kind of fell into the job at the suggestion of a medical school classmate after returning from Nepal in 1977. Upon completing medical school in 1973 and doing a year’s internship at Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal I headed off to Nepal where I helped set up a community health project a week’s walk from the road. This was a pivotal life-changing experience that saw me dealing with extraordinary diseases, and started me on the path to improvising medical care in difficult circumstances, teaching healthcare workers, and living in a simple setting devoid of 20th century technology.

Reflecting on my years as an ER doc, I found it was a window into observing and dealing with many different kinds of individual health problems. In contrast to many other kinds of medical work I had to make diagnoses and justify them in the medical record. The emergency room is the ultimate complaint department. No one comes in to say “Hi, I’m fine, I just came in to say hello.”

The vital signs for a patient there, pulse, blood pressure, temperature and whether they were rousable or not, dictated how fast I had to act. There is a range for what is considered a normal vital sign. I had a ‘rule of fours’: 4 minutes without air, 4 days without water, and 4 weeks without food. If you weren’t breathing I had to act quickly or I would be filling out a death certificate.

What if the country is the patient? What are the virtual signs to consider? Hopefully readers recognize how alive people are in the nation matters. Or what are the mortality rates. And what is a normal mortality rate for a country? Geoffrey Rose, who wrote the seminal: The Strategy of Preventive Medicine began the book by saying there was no “biological reason why every population should not be as healthy as the best.”

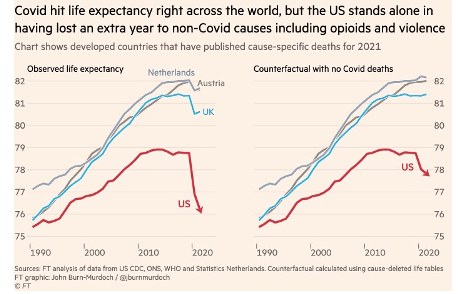

Last month’s blog pointed out how the United States is far from having normal health. Could this be a population health emergency as I suggested? COVID might also have been considered such; the U.S. had the most cases and deaths in the world suggesting the country did not deal well with this disaster.

Consider how some countries have managed public health emergencies. With COVID China enforced a massive lockdown that only ended late last year. Disastrous consequences were predicted but to the present, out-of-control deaths have not occurred. The U.S. had a much more variable response that was clearly not effective. During the 1950s and 60s cold war with Russia Americans build homes with bomb shelters in their basements and did duck and cover training in schools should there be a nuclear bomb explosion. These days with mass shooting being common occurrences in the U.S. there is still no national response.

In recent history there have been two major public health emergencies, meaning that mortality rates rose significantly. When the HIV/AIDS crisis hit Sub-Saharan Africa in the late 1980s, mortality rates rose precipitously. When pharmaceuticals were found to be effective in managing the disease, their use there lagged because of costs. In 2003 America instituted the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) which delivered low cost drugs to many in Africa with attendant mortality reductions. A success story.

The other public health emergency began in 1991 when the Soviet Union collapsed, and Russian life expectancy dropped quickly and profoundly. The drop was biggest in Russian men, and less in women. Reasons were what we might call today “deaths of despair.” The term has come into common use in the United States in referring to the increase in deaths of middle-aged White men over the last few decades as they succumb to suicides, and mortality from alcohol and drugs. Such men are predominantly those with less education who blame themselves for not achieving the American Dream, namely becoming rich which is considered by many Americans as a right. In Russia the most vulnerable were single middle-aged men who drank themselves to death as they despaired over the loss of the support they had enjoyed in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. In the over 30 years since then, Russian life expectancy has almost recovered and rejoined where it was in 1991. Most Russians have been unaware of this profound tragedy as the media did not dwell on the rise in mortality.

How might the next American population health emergency unfold over time? Given our failure with the COVID-19 pandemic, we are unprepared for the next contagion. Serious emerging infectious diseases have been predicted for decades. The U.S. response has been to cut funding for public health efforts at the national, state and local levels. The country spends a scant proportion on social expenditures which have much greater impact on health outcomes than those for medical care where the U.S. spends about half of the world’s total.

Recall the graph from last month (above) where life expectancy in the U.S. fell behind other rich nations in the 1980s and then stopped improving in 2010 before beginning its steep fall in 2019. Covid is not to blame for if we subtract COVID deaths we still see the trends over the same time. U.S. life expectancy is now where it was in 1996.

Could we be on the path to what happened in Russia? After the breakup in 1991 they jumpstarted to a capitalist system. Outside experts advised them to liquidate state assets at fire-sale prices that quickly led to their oligarchy. Immediately these profiteers joined the Forbes billionaire list. Russia’s rise in mortality can be causally linked to the country’s rapid rise in income and wealth inequality.

The United States has had a huge transfer of wealth from the bottom 90% to the top 1% since the early 1980s. Robert Reich, former Secretary of Labor, points out the theft of $50 trillion that would have gone to paychecks of working people. Trillion with a T. There are various reports on where the wealth lies. The U.S. Federal Reserve reported that at the end of 2022 the top1% of households held as much wealth as the bottom 90%. As the rich die they will pass on their wealth to subsequent generations. It won’t trickle down. Inequality will massively increase. Our oligarchs have outdone Russia’s!

Could I extend my ‘rule of fours’ to triaging a population health emergency?

Four months of waiting to act after the ominous signs.

Four years of continuing mortality increase

Four decades until the last human succumbs.

What should the response to the U.S. population health emergency be? Should stopping the steal become the national priority? This is political and the subject of next month’s blog.